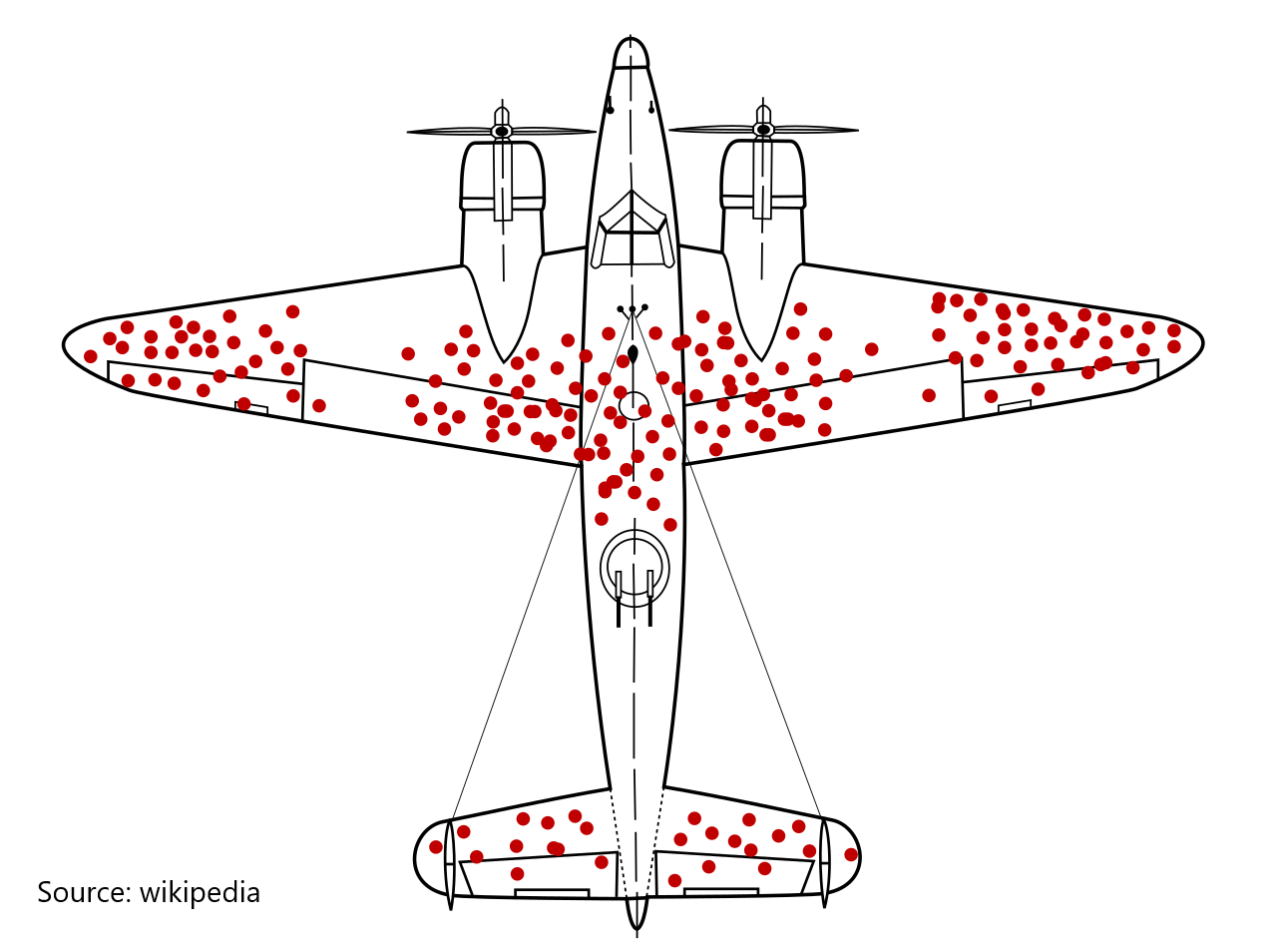

The information gathered during the analysis had made it possible to determine that there were generally several bullet holes in the fuselage, but very few on the engines. The image below depicts a hypothetical damage distribution for aircraft returning from combat. The red dots indicate the location of the bullet holes.

Based on this data, the first instinct of military authorities was to further protect the affected areas, i.e., the fuselage.

Abraham Wald, a statistician employed by the research group, however, came to a very different and unexpected conclusion.

According to him, the additional protection should be concentrated on the areas that were hardly affected, such as the engines, and not on the areas riddled with bullets. His reasoning was simple: since you don’t see bullet holes on the engines, they’re probably on the planes that never returned to base. Conclusion: the analysis of the army officers was biased by the surviving planes.

This survivorship bias is common in the investment world. Here are some examples.

1. Stock market “experts”

You are a member of an investing forum where participants gather to discuss strategies. Many do day-trading and others trade options. Some participants even show impressive returns. You conclude that investing in the stock market is relatively easy and very profitable. Warning: You are dealing with survivorship bias! Investors who failed have certainly left the forum while those who have achieved mediocre returns probably no longer publish their performance. On the forum, you don’t see all those “day-traders” who failed and disappeared.

2. The “if I had”

I frequently hear this type of comment: “If you had bought shares of Apple at the height of the tech bubble in 2000, you would have lost 82% of your investment in a few months. However, those same stocks bought at the top of the bubble would have given you an 12,000% return if you haven’t sold anything until today. Don’t be worried if your stocks drop heavily. Be patient.”

This example is a typical case of survivorship bias. We isolate a successful case while neglecting the failure cases. I’m sure you can name a significant number of stocks that have lost 80% of their value and never recovered.

According to a study carried out by J.P. Morgan in September 2020, 44% of companies that have been included in the American Russell 3000 index since 1980 have experienced a permanent decline of more than 60% in their value from their peak.

3. The new Amazons

Amazon is an exceptional stock market success. Several years ago, Amazon adopted the strategy of investing aggressively in order to grow and expand its leadership position. Using this strategy, Amazon’s net profits and free cash flow have been relatively weak, even negative, for several years.

Today, Amazon has proven the effectiveness of such a strategy. In hindsight, it was justifiable at the time to pay a high valuation multiple to buy Amazon stock.

For several years, I have had the impression that many companies have tried to replicate Amazon’s strategy of investing in growth at the expense of profitability. Investors in these types of companies often use the case of Amazon to justify their position.

Using the example of Amazon is a survivorship bias. Amazon has certainly done well, but there are also a significant number of companies that have failed using this strategy.

Conclusion

In investing, we often hear about success stories, but very little about failures. In my opinion, investors who want to be successful should spend a good proportion of their time examining the failures. This less-published information is very valuable.

Avoid survivorship bias and remember to always consider what is less evident. This will give you a better representation of reality.

Jean-Philippe Legault, CFA

Financial analyst