I am therefore taking the liberty of completely republishing this blog, which appeared originally on February 26, 2021, and which seems to me to be even more topical these days:

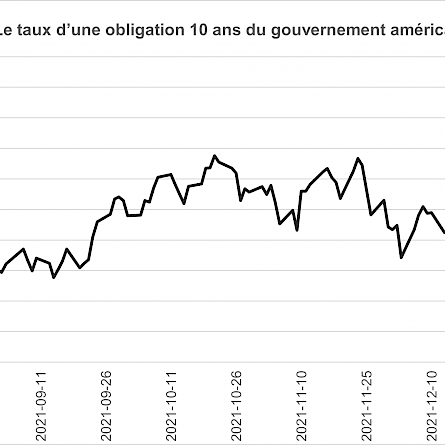

“In recent weeks, interest rates have risen significantly. For example, in Canada, the 10-year government bond rate is currently at 1.47%. You may tell me that it is still very low. Everything is relative in this world and the recent rate is more than twice that of last January (0.68%). In the United States, it’s essentially the same phenomenon: the 10-year government bond rate is almost 1.55%, compared to 0.92% at the beginning of January and 0.64% at the beginning of last September.

The stock market tremors of the past few days are likely related to these interest rate hikes.

On that note, I thought I would talk about the importance of long-term interest rates in valuing stocks. Because, it bears repeating, the valuation of any financial asset, from works of art to bonds to real estate, is dependent on the general level of interest rates. The higher the interest rates, the lower the value of the assets and vice versa.

What is perhaps less known and less obvious is that not all securities are necessarily affected equally by a rise in interest rates.

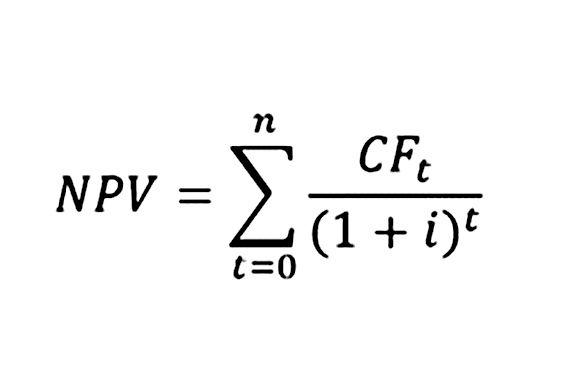

First, the value of a financial asset is the sum of the future cash flows that this asset will generate during its “life”, each of these flows being discounted at its net present value. The formula is:

In this formula, we can see that the higher the interest rate (i) used to discount cash flows (CF), the lower the net present value (NPV).

In this formula, we can see that the higher the interest rate (i) used to discount cash flows (CF), the lower the net present value (NPV).

But a phenomenon that is perhaps less well understood is this: the further into the future a flow (CF) is, the more a change in interest rates will have an impact on its present value.

For example, consider two assets that each offer to pay out $1 million in the future; the first asset will pay it in three years, the second in 10 years. Applying an annual interest rate of 1.5% to these two assets, here is the value we would obtain:

Asset 1 = $1M / (1,015)^3 = $956,317;

Asset 2 = $1M / (1,015)^10 = $861,667.

What would happen if interest rates went up and we used a rate of 2.5% instead of 1.5%? Of course, the value of each asset would decline, but which would decline the most? Here is the answer:

What would happen if interest rates went up and we used a rate of 2.5% instead of 1.5%? Of course, the value of each asset would decline, but which would decline the most? Here is the answer:

Asset 1 = $928,599, a decrease of 2.9% from the previous example;

Asset 1 = $928,599, a decrease of 2.9% from the previous example;

Asset 2 = $781,198, a 9.3% drop from the previous example.

This example demonstrates the greater impact that an interest rate fluctuation has on longer-term assets. It is for this reason that the value of a 30-year bond fluctuates much more than that of a five-year bond. This is also the reason why shares of companies on the stock exchange, which are also long-term assets, can be significantly affected by increases and decreases in interest rates.

Regarding stocks, I would argue that high-growth companies, as well as those which offer hope of future profits, but which are not yet profitable, will be even more affected by a rise in interest rates than mature companies whose growth is not very fast and which are already very profitable. In the first case, the profits are relatively much more distant in time than in the second case.

This, in my opinion, is one of the reasons that would explain the fact that it is the unprofitable, start-up or fast-growing companies that have performed best on the stock market in recent months: interest rates had fallen significantly at the start of the pandemic and in the months following the first wave. In theory, the recent rate hike should have a similar opposite effect. In my opinion, this is a warning to investors who own securities of start-up companies or are not yet profitable.”